Wednesday, May 8, 2013

What do Chicano Art, Empowerment, and Aztlán mean to YOU?

If you're not an artist and you're not Chicana or Chicano, why should any of this mean anything to you?

The answer is: we all need an Aztlán.

Aztlán is not a static concept; it grows, it learns, it adapts.

"As a metaphorical palimpsest Aztlán will continue to change and be redifined by succeeding generations of Chicano scholars, perhaps never completely erasing its earlier definitions" (Watts p.320).

Art is an outlet to express the frustrations of a peoples who feel like they have been forcefully silenced. Chicano art has revealed frustrations about society, racism, economic injustice, education, sexism, among other subjects. Art brings people together, through shared feelings of frustation, love, and pride.

Artists like Patssi Valdez and Harry Gamboa Jr. have written on the palimpsest that is Aztlán, to include themselves and people like them, whether the be women or the urban inhabitants of east Los Angeles.

Aztlán represents pride in one's own history and culture, but more importantly the realization that it is enough.

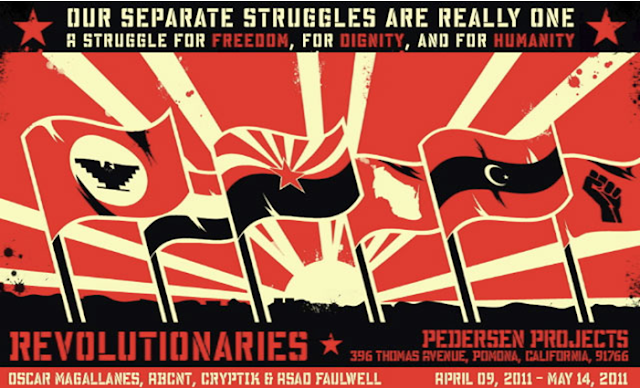

Today, Aztlán brings to mind the American southwest, the mythical land that Chicanos claim their real home. still Perhaps one day though, Aztlán will include all the people's of the world and we will realize we're all fighting for the same things: justice, freedom, and humanity.

Gamboa, Watts, and Goldman

How does Harry Gamboa Jr. tie into our analysis of Aztlan as a palimpsest and Chicano iconography?

Gamboa is another great example of the changing times, interests, and struggles Chicano communities face everyday. Issues that the Chicano communities were plagued with were seldom given importance by the dominant anglo culture of the United States. These issues also changed as years went by.

The changing Chicano culture was especially apparent during the 1970's as many young Chicanos and Chicanas protested the Vietnam War.

Gamboa's style of expression was different, it was weird, and it was strange, but most importantly it was powerful. Gamboa captures the emotions of his audience in a very special way and he designed a new urban Aztlán, where the troubles of Chicanos and Chicanas are very much like our own today.

Gamboa's style of expression was different, it was weird, and it was strange, but most importantly it was powerful. Gamboa captures the emotions of his audience in a very special way and he designed a new urban Aztlán, where the troubles of Chicanos and Chicanas are very much like our own today.

These two videos are one example of how Aztlán is a palimpsests and how artists, such as Gamboa, have written over to adjust to a new, changing generation of Chicanos. While times have changed, it doesn't mean that Chicanos and Chicanas want to disassociate themselves with their rich history and culture. Instead Aztlán adapts to include more people, with different interesets, backgrounds, and different conflicts.

Aztlán represents the battle against "a history of cultural stereotypes of Mexican Americans as violent, passive underachievers, whose lack of success in achieving the 'American Dream' could be traces to the fundamental flaws in their historical and cultural make-up" (Watts 306).

New or old, same or different approaches on Chicano issues all share recurring themes and ultimately, they also share the same goals: Chicano and Chicana empowerment. Artists, like Gamboa, use their works to communicate to their audiences, Chicano and non-Chicanos alike, that they're not alone in their struggles, in their fight for justice.

Gamboa, in particular, has explored many mediums to communicate with his audiences. His use of photogrpahy, film, multimedia is an example of the use of iconography for Chicano empowerment. Gamboa represents the diversity of Aztlán, the opportunity for change.

Valdez, Watts, and Goldman

How does Patssi Valdez play part into the

idea of Aztlán as a palimpsest? What does Patssi Valdez have to do

with Chicano Iconography on self-determination, race, ethnicity, and class?

Patssi Valdez, both as a member of ASCO and as an

individual artist, has used Aztlán as a palimpsest and used Chicano

iconography to promote Chicano self-determination. To begin with, a palimpsest

can be defined as "a manuscript or piece of writing material on which the

original writing has been effaced to make room for later writing" or

"something reused or altered but still bearing visible traces of its

earlier form." Iconography is "the use or study of images or

symbols in visual arts" (definitions courtesy of goole.com) Valdez, like many other Chicano artists has

developed and built on the idea of Aztlán to express her frustration and

challenge the norm. While Valdez use of Aztlán

as a palimpsest has taken her on a particularly unique road, with a different

approach and style, it has nonetheless taken on a journey of confronting the

barriers than prevent Chicano growth and visibility. Valdez artistic style, especially during her

years as a member of ASCO, was different from other Chicano artists who also drew

their inspiration and traced their roots to Aztlán. However different her approach, it still

“[perpetuates] its mythic status as a location of Chicano identity” (Watts

305). Ultimately, Valdez is tackling

issues of the Chicano communities. Valdez

understood that “the dominant culture persistently considers cultural traits

differing from its own to be deficiencies”

(Goldman 170) and used her work "to show, how in response to

exploitations, artists have taken an affirmative stance celebrating race,

ethnicity, and class" (Goldman 167).

Valdez was in a great position to challenge

sexism because she was one of the few Chicanas who ventured out into the arts

and was able to make a name for herself. The Chicano Movement was able to use the

concept of Aztlán as “an organizing metaphor for Chicano Movement activists,

allowing them to unite heterogeneous elements under one political and social

ethos of self identity and community empowerment, while advocating racial

solidarity, social, and political change for Mexican-Americans” (Watts 306). Gender,

on the other hand, was largely ignored.

This led many Chicanas to develop a “Chicana feminism, a feminism which

reaches out to the Chicano community, remaking the Movement as it seeks to

include those female and queer voices silenced in its discourse” (Watts 307). Chicana feminism “[includes] a focus on

gender as well as race and oppression” (Watts 307).

Tuesday, May 7, 2013

Harry Gamboa Jr: Provocateur

Chicano artist Harry Gamboa Jr. also got his start with ASCO, the east Los Angeles based performace group.

Gamboa and ASCO acquired much attention because the four original members tackled issues that they confronted everyday as young Americans of Mexican ancestry. Chicanos had been ignored for too long; inspired and encouraged by Black American's resistance and empowerment, Chicanos also fought for and asserted their rights as American citizens. Gamboa was politically active during his earlier years, especially during his high school years. He participated in the Chicano Student Walk-Outs and fought for Chicanos' rights to adequate education.

Outside of school, Gamboa along with his good friends Gronk, Patssi, and Willie were taking on some of the most ignored and frustrating issues that plagued Chicano communities.

Gamboa photographed and directed many of the performances and statements made by ASCO. Unique to Gamboa, and ASCO's work, was the direction that they took their art in.

It was popular, and still is, for Chicano and Chicana artists to take from their rich culture and history, and project their interpretations as murals, paintings, or other works of art. Gamboa had different ideas.

Gamboa did not limit his creativity to one medium; he explored photography, film, production, performance, multi-media. Gamboa challenged and continues to challenge misconceptions and stereotypes of the Chicano and Latino communities of the United States. Most notably, he explores contemporary and urban issues of Latino communities using not so traditional mediums.

The beauty of Gamboa's art expression lies in that each piece of his work is able to connect the people, the issues, and the time to the same issue: misrepresentation.

Gamboa tempers with the concept of perspective over and over, challenging the ideas, concepts, stereotypes, and assumptions about the Chicano community.

(Recurring theme in Gamboa's work: Thug, Tough, or Tame?)

Gamboa was able to provoke feelings of frustration, anger, hate, sorrow, despair, joy, hope, triumph, and a myriad of other emotions as he ventured into territory where few other Chicano artists had gone.

Gamboa provoked outrage in some Chicanos, outrage that led to questioning not only the socio-economic conditions Chicanos were battling, but the harsh reality of the racism and prejudice that kept them there.

All Odds Against Me: "Woman, Poor, and Mexican"

http://youtu.be/6VfWyZnzDDQ

Culture Fix: Judithe Hernandez on the Role of Women in the Chicano Art Movement

"The very fact that when you look around the room and when you look at the brochure there are less than a dozen women that are participating in the show and that have participated in some of the other PST shows I think illustrates the fact that women- women were present but their role I think, was not as well recorded as it might as been because they were women."

-Judithe Hernandez

Monday, May 6, 2013

Patssi Valdez: Art Innovator

Chicana Patssi Valdez has been redefining and challenging art standards to include Chicano and Chicana artists since the 1970's.

Patssi Valdez is an east L.A. based artist who got her start during her late teen years.

Valdez was one of the main members of the art collective known as ASCO, an east L.A. based young group of artists that struggled with the harsh reality of being a Chicana or Chicano in the United States. ASCO's original members include Harry Gamboa Jr, Gronk, and Willie Herron. This particular group of young people were repulsed by their surroundings, the poverty that seemed to engulf their people and themselves, and the lack of opportunities for young Chicano artists during the 1970's and 1980's.

During the 1970's many young people protested the Vietnam War, not only for the brutality of the war, but also the draft that forced (mostly) young men to enlist, many of whom did not return alive.

Valdez was in particularly interesting position during her early years as an artist challenging the realities around her, because of her gender. The Chicano Movement of the late 1960's - 1970's was successful in raising awareness about the "oppression and exploitation of and racism against the Chicano people" (Watts P. 306). However, "one of the key failings of ... [the] early Chicano Movement itself was its denial of the equal importance of the women within the revolution" (Watts P. 307).

Valdez, as a core member ASCO, had a unique opportunity to expose the potential of Chicana art and tackle issues pertaining to Chicanas. Valdez was the only female member of the art collective ASCO and through her interpretations was able to challenge and revolutionize the way women were seen. Valdez was not shy in exploring alternative interpretations of popular female icons, like the Virgin de Guadalupe, patron saint of Mexico. She openly challenged the roles women played in family, society, and even in religion at a time when women's contributions were being ignored and the Chicano Movement and Chicano art was largely male produced. Valdez not only spoke out against racism, discrimination, and injustice, but also confronted sexism.

(Day of the Dead. THE WALKING MURAL.Patssi dressed as the Virgin)

The "Plan"

"In the spirit of a new people that is conscious not only of its proud historical heritage but also of the brutal 'gringo' invasion of our territories, we, the Chicano inhabitants and civilizers of the northern land of Aztlán from whence came our forefathers, reclaiming the land of their birth and consecrating the determination of our people of the sun declare that the call of our blood is our power, our responsibility, and our inevitable destiny."

El Plan Espiritual de Aztlán

Rodolfo "Corky" Gonzales

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)